I’ve been a fan of Charles de Lint’s work since I was a young teenager and picked up a copy of Moonheart. Moonheart probably isn’t for younger readers, as it includes some pretty graphic sexual descriptions and some pretty dark situations, but minus the fairly adult sexuality most of de Lint’s work would easily appeal to younger readers. The central idea of all de Lint’s books is that there exists, somewhere between the corner of our eye and just to the left of reality, an Otherworld peopled with all manner of fairy-tale creatures, from goblins and fairies to darker things: soul-stealers and giant spiders and evil spirits. A great deal of his early work draws on the mythologies of the British Isles and Ireland, but the last decade or so he’s turned more and more to the mythologies of Native America for inspiration.

Moonheart. Moonheart probably isn’t for younger readers, as it includes some pretty graphic sexual descriptions and some pretty dark situations, but minus the fairly adult sexuality most of de Lint’s work would easily appeal to younger readers. The central idea of all de Lint’s books is that there exists, somewhere between the corner of our eye and just to the left of reality, an Otherworld peopled with all manner of fairy-tale creatures, from goblins and fairies to darker things: soul-stealers and giant spiders and evil spirits. A great deal of his early work draws on the mythologies of the British Isles and Ireland, but the last decade or so he’s turned more and more to the mythologies of Native America for inspiration.

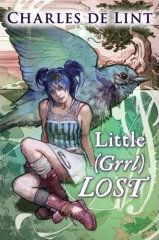

Little (Grrl) Lost finds de Lint once more exploring the more familiar terrain of European fairy tales with the story of a Little named Elizabeth Wood, her Big friend T.J. fresh from the farm, and the great big world of gnomes, fairies, goblins, and other magical beings they find when they take a step away from the safe, comfortable world the girls’ parents had created for them. A Little, it turns out, is a 6-inch tall person, and a whole family of them are living between the walls of the suburban house T.J.’s family moved into when their family farm failed. Full of punk energy and teenage angst, Elizabeth runs away from home far enough to meet T.J., in whose room the front door of their home is. Frightened by the discovery of their girl by the Big, Elizabeth’s parents quickly move, and in search of clues as to where they might have headed, T.J. and Elizabeth try to contact an author, Sherri, whose books about little people seem real enough that the girls think she might just know about real Littles like Elizabeth. And then things start to go wrong…

Little (Grrl) Lost is, like all of de Lint’s novels, a pretty fun read, and I imagine that any fantasy-minded young teen would enjoy it. Long-time readers of de Lint will probably enjoy it as well, although at this point de Lint has settled into a pattern (maybe even a rut) with his characters and plot elements that take a little of the fun out. For instance, one of the recurring themes in de Lint’s books is sexual abuse, especially of children. In other books, he’s delved deeply into the trauma and personal consequences of victimization. At the beginning of Little (Grrl) Lost, T.J.’s parents mention a man harassing girls on the main drag of their suburban center, and T.J. of course has a run-in with him a few pages later, but it’s incidental and does nothing to forward the plot other than give T.J. and the readers a scare. He could have been left out and nothing would change about the book — except de Lint doesn’t seem able to leave the topic alone.

Another issue I have with this book is one that’s been building in much of de Lint’s later work, which is the off-hand and almost bored way his characters react to their discovery of the supernatural. I think de Lint himself is bored with depicting the surprise that is natural when, say, a 6-inch person steps out of your baseboard or a 2-foot gnome appears out of nowhere. Earlier books revolved around the difficulty people have wrapping their heads around things that defy all their ideas about the normal, natural, and rational; nowadays, though, characters just seem to take it all in stride, often without a second thought. “Oh,” they seem to say, “faeries are real. Neat. Hey, how’s your stock portfolio doing for you, anyway?” It’s as if magic has become so everyday for him that he’s forgotten how to be amazed by it.

These aren’t really deal-killers, though; they probably wouldn’t be noticed by someone who is just being introduced to de Lint’s work, and there are quite a few good reasons to introduce yourself. Nobody imagines and fleshes out the Otherworldly as well as de Lint, and the underlying message of all his books is open-mindedness, awareness, and community — not a bad message for young readers and adults alike. The characters in Little (Grrl) Lost learn to stand up for themselves, and to stand up for others, and there’s nothing wrong with that, either. For readers from 11 or 12 to their mid-teens, I’d recommend it, especially if they’ve already started getting into fantasy — de Lint is head and shoulders above the typical swords-and-sorcery stuff out there. Older readers might also enjoy it, although I fear de Lint’s dialogue and his characters’ reactions might come off as a little corny.

If I were using a star system, Little (Grrl) Lost would get three stars out of five — a good solid book with a few non-critical flaws.

Leave a Reply